In the 1960s, the strong Icelandic ‘rímur’ (rhymes or ballads) tradition made way for a ‘free form’ modern poetry, which itself was part of an international revolution within poetic language. At the age of nineteen, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir (born 1950) appeared at the crossroads between modernism and the 1970s confrontation with modernism’s inaccessibility, with the modernist poetry collection Sífellur (1969; Continuances). The meaning of words should now be clear to anyone, poems should be accessible and under common ownership, the style should be extrovert, and the message should be easy to understand. The collections that followed, Þar og þá (1971; Then and There) and Verksummerki (1979; Evidence), thus celebrate the accessible poem; as Þar og þá puts it: “let us write extrovert poems”. A clear awareness of literature as literature meets an ironic self-awareness, which in turn struggles with overwhelming emotions in which the theme of separation dominates.

The poet describes the writing of Tímaþjófurinn as a very long and complicated process. In a newspaper interview from 1986, she says: “The pages simply mounted up in small heaps in my room, and I was walking on them by the end. My desk had long been far too small, so I had to use the floor as well, and the whole thing went from being a novel to a kind of happening. I can remember one time when I got out of the bath, a few pages from Tímaþjófurinn got stuck on the soles of my feet”.

Tímaþjófurinn is the pinnacle of Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s oeuvre so far, the remarkable and insightful articulation of a well-known motif: the unhappy love affair that develops into fiery passion and longing, like the suffering experienced by young Werther more than two hundred years earlier. It is clear that the poet has found her own means of expression here, after her battles with modernism and socialism. The struggle between irony and subject matter seems to have been sorted out and replaced by a confident grasp of language, in which internal conflicts work together with the subject matter, yes, and even take it over: the conflict within the text has now become the subject matter. With Tímaþjófurinn, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir broke through to both the public and the critics.

The first collections of short stories, Sögur til næsta bæjar (1981; Stories Worth Re-telling) and Skáldsögur (1983; Novels), are both clearly marked by neo-realism and have a critical, socialist point of view, but they nevertheless do constant battle with an ironic distance that shifts, at times, into parody. In Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s first novel, Tímaþjófurinn, (1986; Eng. tr. The Thief of Time), lyricism merges with prose and narrative embraces the poem. In the cradle that is thereby established lies the main character of the book, Alda (the name means ‘wave’), rocking back and forth.

Tímaþjófurinn is a love story, but the love affair itself is soon over; the pain, loss, and feeling of rejection, on the other hand, continue for a long time. Alda, is a secondary school teacher, comes from a good family, and is very beautiful, and she falls in love with her young colleague with whom she spends hundreds of ardent days together. But then it is all over: with icy-cold resolution her lover, Anton, condemns their relationship, and the book focuses mainly on the abandoned Alda who wanders aimlessly about in a sea of heartbreak and memory. In Tímaþjófurinn, two Aldas are juxtaposed: on the one hand the main character, Alda, who has reserved a grave for herself in the old churchyard, on the other hand her alter ego, a stillborn sister of the same name, another Alda who is already buried in the churchyard. This divided self-image appears in the body and in bodily metaphors.

Beneath the face, beneath the surface and the visible, there lies glowing, naked flesh, the emotions that, like disgusting entrails, can never be revealed. “The thing is that someone who doesn’t keep her composure isn’t just named, she’s open as well; her revolting entrails are there for all to see. No-one could bear a person of whom they’d had that sort of view, unless he were a trained surgeon”. By revealing her emotions to the world, Alda opens up her body to decay. Her body lets her down after the break-up; indeed, Alda’s body becomes just as broken-down as the relationship: her hips start to hurt, and she loses the power of speech. Interpreted symbolically, it is the dead sister’s perishable, rotting body that takes over Alda’s beautiful, living body. The break-up is a farewell to herself or, rather, to the embellished self-image that ensures she “looks so neat and nimble-oh, with every hair on her head in its proper place, and wearing the red knitted dress which does not conceal the body’s perfect sculpturing”. The body is seen as a sculpture, a statue, an image, not as real, mortal flesh. Seven years later, Alda avoids Anton; she does not want him to “find out what a sorry state she’s in”, and to smile “through sympathy with me in my old age”. The theft of time appears very clearly in the body: Anton steals Alda’s youth and beauty, and she grows old in a way that is out of synch with time.

Like others of her generation, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir has moved between literary genres. In addition to prose and poetry, she has written two plays for television, Líkamlegt samband í norðurbænum (1982; Physical Contact in the North Part of Town) and Bleikar slaufur (1985; Pink Ribbons), which, with their ironic, tragic-comic depiction of Icelandic (consumer) society, follow in the footsteps of the short stories. At the start of the 1980s, she was the editor of a cultural programme on television that gained a lot of attention. Steinunn Sigurðardóttir has also written a biography of the former President of Iceland, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, Ein á forsetavakt (1988; Alone on the President’s Shift), and has translated novels and plays.

That which, above all, characterises the reading and discussion of Tímaþjófurinn is the manner in which the language submits to the subject matter: form is just as important as content, and words are weaved into events just as events are weaved into words. An example of this can be found in the passage where Alda shows her lover the potted plant that she tends with great care, a flower that by virtue of its name, “impatiens”, is a symbol of Alda’s love for Anton. The text slides from a description of a blossoming Busy Lizzie in a window to a love that is blossoming: “Lizzie, which is called Busy or ‘impatiens’ in foreign languages … burst forth into manifold blossom at about the time the sunlight was shortest. Christmas-Teddy gazed in astonishment at a hundred pink Lizzie flowers. He didn’t think I could do it, as he said.

My love first burgeoned in this room

and outshines others in the window

with eighteen flowers and all kinds of bud.

That’s a charming plant of yours say my visitors

not knowing that this is love”.

The author seizes on a well-known metaphor here and turns it into an original declaration of love. Like Alda, the impatient Lizzie is impatient for love, and in the line “That’s a charming plant of yours say my visitors”, one hears a gentle echo of the rhythm of the Song of Songs in which flowers and flower metaphors often turn up in descriptions of love and impatient longing. And the flower metaphors and flower word-play become even more focused with the arrival of heartbreak. Alda covers flower bulbs with soil, and at the same time conceals her love and her hope that Anton will come back to her:

In September I plant the autumn bulbs. In their usual place. The leaves are falling in splendour.

Blow, blow, autumnal leaves, away, away!

I saw you first a year ago.

Those little bulbs. What will they be when they come up? They will be your eyes.

Blue scillas. My garden. Sullied by your eyes. Hushabye scilla-bulb.

When the blue scillas sprout I’ll tear out your eyes as they persecute me one after the other in the spring.

Alda would like to discard her love for Anton as she does with the flowers she tears from the soil, but at the same time the flowers are an unpleasant reminder of Anton, in the form, moreover, of a bulb. Words flow together and metaphors merge into each other, only later to disappear, to dissolve in eyes that are plucked out when spring comes along. Flower bulbs become flowers, which become eyes, which are then plucked out and become words, which merge together and burst out in wordplay. In this way, style is fused with subject matter: language, as the means of expression, becomes meaningful in itself and by virtue of the close interplay in which it continually becomes one with the subject matter, the story.

The novel Ástin fiskanna, (1993; The Love of the Fishes) positions itself in continuation of Tímaþjófurinn. The main character and first-person narrator, Samanta, has a brief erotic affair with a man but then decides to end it, and flees from him and from love. The novel enters the world of fairy-tales: “I think back to our first meeting, when I was in the incredible position of living in a city and having two peacocks for company”, says the ‘princess’ and main character Samanta. At the same time, Samanta is Sleeping Beauty since “right up by the door there grew tall, orange-coloured roses”, and when she says goodbye to the ‘prince’ (who is called Hans, like Clumsy Hans from the fairy tale), the peacocks stand one on each side of the door like guards, and it seems to her that “they bowed their heads, first one then the other”. But the fairy-tale does not end in the traditional manner with a promise of eternal wedded happiness: they go their separate ways, and the woman realises that the fairy-tale does not end in this way by itself:

“When I listen more closely, I understand that one who sends his or her loved one away, northward bound, does not necessarily reap endless isolation, even though that is the case for me. I now understand that one who sends a man northward on his own could just as well receive his eternal company. But no-one knows what produces this result: perhaps it is thanks to the bird-song one hears when sitting on a stone by the North River”.

Here it is Samanta herself who takes her fate in her own hands and rejects love, unlike Alda who falls victim to a mess of emotions. Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s female heroines become stronger and more stable in every book. Like the female ghost that refuses to be subdued, her female heroes have greater and greater powers in each new form they assume. Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s novel Hjartastaður (1995; Place of the Heart) builds up a chain of strong, independent women who undertake a symbolic journey into the past and into nature in order to take control of their lives and become reconciled with their self-images. In every new book, which consolidates the author’s position, her female heroes become stronger and more stable, both as controllers of their own fate and as characters.

The use of the fairy-tale genre, as in Ástin fiskanna, represents a new, post-modern kind of narrative. Along with a new narratological perspective, there is a return to the primal stories and myths. The present day is seen in terms of legend or myth, and at the same time there emerges a temporal tension, a kind of temporal confusion. Tímaþjófurinn plays, to some extent, with the notion of the relativity of time; the hundred days Alda had with Anton cover the whole of her life, while simultaneously contracting into moments that are far too brief. Alda’s time is over when the relationship ends: she feels like a woman who has grown old too soon, and she eventually takes her own life, putting an end to her time. In this way, Anton becomes a time-thief within this temporal chaos: he steals Alda’s time and throws it into confusion, altering and distorting it.

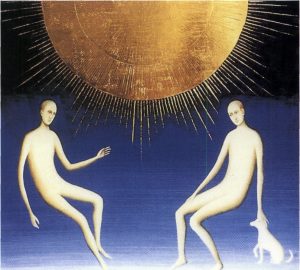

The theme of separation was already present in Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s poems, and it makes an appearance in the short story Ástin fiskanna (1993; The Love of the Fishes), Tímaþjófurinn also demonstrates that the separation theme of her poems is, not least, a form of self-analysis, a search for an (abandoned) self, as in the cycle of poems “Sjálfsmyndir á sýningu” (1991; Self-portraits in an Exhibition).

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s authorship has received a lot of attention, and is characterised by a unique lightness and linguistic playfulness. The combination of isolation with a many-sided self, a theme that occasionally emerges in her poems and prose works, is the result of a reflection on time, its nature, and its transitoriness. In this way, a search for time goes hand in hand with a search for the self: it is a search for a temporal self, for the where and when of the self. In the poetry collections Kartöfluprinsessan (1987; The Potato Princess) and Kúaskítur og norðurljós (1991; Cow Dung and Northern Lights), which appeared in the wake of the novels Tímaþjófurinn and Síðasta orðið (1990; The Last Word), the conception of time becomes more sophisticated: the self’s search for itself changes and is experienced in time and space rather than through an inward perspective. The poet’s search for the time that was so effectively stolen in Tímaþjófurinn continues here, in an even more focused manner. Perhaps ‘search’ is not the right word in this context: a fight or struggle with time expresses better the way in which time is handled.

The novel Síðasta orðið (1990; The Last Word) parodies Icelandic society as expressed in the affinity of Icelanders for obituaries and memorial articles. Just as Steinunn Sigurðardóttir’s talent came into its own through the language work in Tímaþjófurinn, so Síðasta orðið is critical on every level of both language and text. The nation is characterised through newspaper articles written in memory of a deceased, and is at the same time exposed to critique through parodic use of this genre.

In Tímaþjófurinn, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir had already found a means of nailing time to the wall, continually circling around the same idea, observing it from all sides, and isolating and highlighting it. This is shown extremely well in the poem “Andartakið” (The Moment) in Kartöfluprinsessan, where everything is merely a sign or imitation of the perfect moment.

I cast rays towards

the dark heaven of your eyes.

I took their reflections with me,

as well as the words spoken in silence

and loved you

this obvious moment.

Others were precursors of the one and only

or imitations of it.

In the poem “Tímaskekkjur” (Anachronisms) from the same book, the minutes leap and jump about: they “no longer trot along with the sun”, and “I recently saw one that jumped backwards / and then took two steps forward”, despite the blind creature “that is the driving force in the poems”; and in the poem “Monstera deliciosa á næturvakt” (Monstera Deliciosa on the Night-shift) in Kúaskítur og norðurljós, a sneaky plant turns up, entangles itself in the clock, and cunningly strangles time:

The husband shivers drowsily

as he enters the living room one morning

because the marvellous plants Málfríður cultivated so well

and the clock on the wall

have become entangled in each other

The newest leaf twists, light green, around the minute hand and stops it

at midnight

This cunning plant found a way – and strangled time.

A young plant cunningly grabs all the power. Time is masculine and, like the husband, keeps regular habits, whereas the plant and Málfríður are women who rebel by entangling things and holding meetings at midnight. In this way, the poet anchors herself in time; anchors herself and her many faces that look at the reader, as in the cycle of poems “Sjálfsmyndir á sýningu” (1991; Self-portraits in an Exhibition), in which the many faces shift and change before the reader’s eyes. The self-portraits in the cycle of poems are numerous and ambiguous. They depict all ages and both genders and, thanks to the Icelandic language, even though the self-portraits are of men – a dwarf, a meteorologist, and a fallen angel – the soul or self-portrait, funnily enough, remains feminine: a woman who is trapped in the body of a man and who embarks on small, private rebellions:

Now my soul is the only Icelandic female ghost

still alive, if life is the right word.

It hunts sheep and drives the shepherds of Eyjafjörður crazy.

It is no joke when the ghost whinnies

and flies through the valley with a flayed sheep behind it.

Determined to continually haunt the place.

From the start of her authorship, the image of the self is doubled and multiple, hermaphroditic and ambiguous. “Sjálfsmyndir á sýningu” demonstrates, perhaps more clearly than any other work, the self-analysis that characterises Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who is an important figure in contemporary Icelandic literary life.

The collections of poems resemble a photo album, and if one turns the pages quickly the images fly by at the speed of light and tell a story that always remains out of reach. They leave behind the vague impression of someone analysing themself, twisting and turning, and taking picture after picture of their surroundings in order to observe themself in this mirror of time.

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir

The Dead Woman Lives

Vigdís Grímsdóttir (born in 1953) gained attention with her first two books, Tíu myndir úr lífi þínu (1983; Ten Pictures from Your Life) and Eldur og regn (1985; Fire and Rain), which contain short prose pieces and poetry; but she made her name properly in 1987 with the novel Kaldaljós (Cold Light). It is the story of a little boy who loses his entire family in an avalanche. He is fostered by good people, grows up, and seems to be a normal young man. But his world is cracked and split in two. On the one side there is his life with his parents, siblings, and other relatives; it is his own world that no longer exists. On the other side there is the world of other people, in which he lives as a guest or a foreigner.

The boy gets into the Academy of Fine Arts where his teachers and fellow students are amazed by his originality, but only a handful know that he is systematically working on a large project. He paints enormous pictures, all the same size, one after the other, which he hangs on the wall of his living room, and gradually a huge picture is formed in which one can make out his family in the white snow. When the project is close to completion, the artist locks himself in with it, and when his friends gain entry to the room he is gone: but the last part of the picture is now in place. It shows an image of the artist in the snow: he has disappeared into his own work, is reunited with his family, and has become whole.

The magic realism of Kaldaljós was expressed not only through motifs from folk tales, with flying women and artists who disappear into their own work, but also through a verbal magic that was the diametrical opposite of what the authors of the 1980s felt was the flat and amputated reportage style of the 1970s and of neo-realism. Kaldaljós makes liberal use of repetition, linguistic fantasy, and a mannered style to create a display of verbal fireworks. The repression of death and narrative melancholy bursts out in textual excess: in some passages the language is so over the top that other chapters seem flat in comparison; there is no balance within the language. Read in the light of Vigdís Grímsdóttir’s later novels and poems, Kaldaljós therefore serves, first and foremost, to herald an extraordinarily intriguing authorship.

The young man in Vigdís Grímsdóttir’s Kaldaljós is a ‘child of nature’ in his art, hypersensitive towards his own feelings and, at the same time, unresponsive to external impulses. His inner world is full of beauty and paradox, but he neither wishes nor is able to accept advice from others, and he cannot reflect on and deal with his problems. The cold, white light of detachment and reflection is so threatening and traumatic that when he draws on it, it destroys him. This mixture of anti-intellectualism, romantic myths about artists, and magic realism hit the spot for readers in the second half of the 1980s.

Lion or Lamb

Ég heiti Ísbjörg – ég er ljón (1989; My Name is Ísbjörg – I am a Lion) is not marked to the same extent as Kaldaljós by such extremities of style: the tension or energy that facilitates them is, instead, used to create a figurative and energetic text. The book opens as follows:

My name is Ísbjörg.

I am a lion.

The sword of justice flashes in the air. Darkness. The gilded hilt glitters. Stars rush by. The shiny white blade vibrates. Sparks fly. The sword whirls around me. I do not bow, even though the song is heard:

An eye

for an eye

for a tooth

for a tooth

The first-person narrator, Ísbjörg, tells about life and death in the fullest sense of the phrase, like Scheherazade in The Arabian Nights. Ísbjörg sits in prison and tells her lawyer her story: he is the silent listener to a story that he must and shall believe. Every single word, every single comparison, every episode of the narrative must and shall convince or seduce the lawyer (the reader), since the sentence Ísbjörg will receive depends on this. She has committed murder, but has not confessed to it. Is she guilty?

Ísbjörg is twenty-one years old. She is a prostitute. She has killed an elderly gentleman, her regular, in the office where she used to service him. The weapon is a paper knife.

Ísbjörg’s story is that of a child who becomes the pal and buddy of her parents, who love each other through the child and with her help. The father orchestrates this sick performance until he can no longer bear himself and commits suicide. He leaves a wife and a child who no longer knows who is who. Ísbjörg becomes her mother’s mother, a betrayed child with a complex psyche.

Ísbjörg tells the lawyer her story over the course of twelve hours, and the narrative pattern of the novel follows the pattern of psychoanalysis in which one memory leads to another, and each image emerges from the previous one, until one cannot dig any deeper for the time being. The lawyer listens. Ísbjörg’s story starts off harsh and aggressive: she wants to get the matter over with quickly and seduce the listener in a hurry, as can happen with casual acquaintances and superficial intimacies. But the subject matter is too difficult and all-encompassing: a life-story is a bottomless pit of significance, and her attempt at haste is impeded by the time the story takes to tell. Ísbjörg tries to talk herself away from death, just like the young man in Kaldaljós tries to paint himself away from it. But instead of pushing death away, Ísbjörg’s narrative draws it closer to her, and in the last monologue she heralds her own death: she will not be in the cell when the lawyer returns; her narrative is complete, and the novel ends.

The novel Ég heiti Ísbjörg – ég er ljón was successfully dramatised and staged at the National Theatre of Iceland in the winter of 1992. Two actresses played Ísbjörg: one was light-haired and the other dark, one was gentle and the other cruel. They appeared on stage singly or together, as two sides of Ísbjörg’s character.

Love and Death

A woman in white appears in Ísbjörg’s dreams, a woman who walks along a beach either alone or leading a child by the hand. This is Ísbjörg’s ‘alter ego’. The woman in white is strangely peaceful, as opposed to the storms raging in Ísbjörg’s soul. The peacefulness of sorrow is also felt in Minningabók (1990; A Book of Memories), which contains poems and short prose poems in which Vigdís Grímsdóttir remembers and mourns her father’s death.

The woman in white makes another appearance in the poetry collection Lendar elskhugans (1991; Lover’s Loins), and again she walks along the beach. The first-person narrator obeys her call and sets out on a journey downwards, through a number of levels, and a sense of discomfort begins to seep into the cycle of poems. After having been amongst dwarves on the large plain, the narrator reaches the bottom of a surreal nightmare of violence, mutilation, and the flames of hell. The road back from here passes through a landscape of words and texts: “funny / funny / funny / I have done this before / and yet never / I have jumped and leaped / between their words / marched between thickly overgrown hillocks / rested / in fertile hollows / tested my wing-span / and my gentleness / and slept / and slept / and slept / I must withdraw / go my own way / but it was good / to get lost here”.

The loved one is caressed and kissed, and the narrator dances with him. He is shown great tenderness and love: perhaps he is the father of the children in the cycle of poems. Candles in golden candlesticks are lit and arranged around the bed where he lies naked. Then he is abandoned, surrounded by flickering lights. Women’s love goes hand in hand with much greater suffering and risk. Death and destruction are always close by, and the question of one’s own identity becomes tenser and more anxious, because ‘equality’ threatens to turn into ‘sameness’, and what then is ‘my’ position regarding the other one? These questions continue to be heard in the following novel, Stúlkan í skóginum, (1992; The Girl in the Forest).

Stúlkan í skóginum tells of Guðrún, who is invited for coffee by a woman she does not know, the artist and doll-maker Hildur. It is the first time anyone has invited Guðrún home. She is the narrator, and the reader enters her distinctive conceptual world, which is full of poetry and a love for humanity. Guðrún collects books: she finds her books during the day, in the rubbish bins around town. We only find out later in the novel what impact this has on both her social status and her body odour.

We see Hildur from the outside to begin with, through Guðrún’s eyes. Hildur is an attractive woman, but she is also evil. She has invited Guðrún home and is not planning on letting her leave alive. She needs Guðrún’s heart so that her latest doll may live. The doll is the spitting image of Guðrún, and through the description of the doll we find out what Guðrún looks like. She is monstrous. Her body is bowed, her face disfigured by an incurable skin disease, her skin is bluish, her mouth looks like an open wound because she has almost no lips, her eye-lids are shrivelled and broad, most of her hair has fallen out, and we gradually find out that Guðrún has very little control over her body fluids; discharge flows from her eyes, nose, and mouth, and now and then she sweats a lot. Who feels like identifying with such a person? No-one. But it is too late to turn back, and the reader is forced to settle down in this disgusting mortal vessel.

Guðrún and Hildur are ‘the beauty and the beast’, and just like in the fairy tales, the beautiful one is evil and the ugly one is good. The metaphysical separation between body and soul is the premise for the conflicts that are played out in the text. Guðrún is able to keep her mind clean and poetic only by disowning her repulsive body and, similarly but conversely, Hildur worships her own body but disowns her soul and the divine aspects of humankind. Her artistry is “death”, as one critic has put it, and it is for this reason that she needs Guðrún’s soul.

Elizabeth Bronfen says in her book Over Her Dead Body, 1992, that the reason why the death of a woman is such an important motif in the visual arts and literature of men is that a dead woman in an art work symbolises the two subject matters that neither culture nor language can express, namely death and womanliness. If Bronfen is right, then Vigdís Grímsdóttir’s motif in Stúlkan í skóginum is an eternal provocation and ‘subversion’ of the traditional artistic expression. Because how can a woman sacrifice another woman for the sake of her own art? Does the other woman allow herself to be killed in order to become “the most poetical subject in the world”, as Edgar Allan Poe described the death of a beautiful woman?

This question is raised by the two women in Vigdís Grímsdóttir’s text, and the buck is passed to a third woman. Hildur creeps into Guðrún’s body and changes places with her, because she wants to find out how such scum appears in the eyes of other people. Guðrún is locked up in Hildur’s flat, in Hildur’s body, where she finds a letter addressed to the artist: and she reads it even though she feels bad about it. The letter is from the author V. G. (Vigdís Grímsdóttir), who tells Hildur that she is welcome to make use of the object Guðrún; she herself has given up on writing about her, as there can hardly be enough material for a literary work in the head of such a loathsome woman. She is a more suitable subject for an art work. The female rhetorician hands over power to the female artist and commands her to kill the book collector and reader Guðrún. But she does not want to die, and the ending is left open: we are unable to decide who the author is and who the character is. We are also denied the chance to decide which of them died.

Power against Love – Love against Power

Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir (born 1938) made her debut as a writer of fiction with the short story collection Af manna völdum (1982; Works of Man). The stories take place in Reykjavík, Spain, and Switzerland, and revolve around the theme of power or, rather, different people’s experiences of power. The short story collection received attention, not least because of its distinctive and intense style, based on short sentences and a fast pace.

The prize-winning novel Þel (1984; Temper) is also a European novel that takes place in Iceland, in Franco’s Spain, and in de Gaulle’s France. The first-person narrator and main character is a man who, the night after the funeral, reflects on the sudden death of his friend. The deceased was both his best friend and his worst enemy. The narrator tries to understand – without really feeling like embarking on a serious investigation – why they both ended up in their own private hell. The un-cooperative nature of his narrative, its withholding of information, makes the novel feel like a psychological thriller or detective story.

A large part of the novel Þel takes place in Franco’s Spain in the early 1960s. The ‘apolitical’ aesthete Einar experiences both love and the fight against Fascism when he meets the intelligent and strong-willed Yolanda, who is studying in Spain but comes from South America. She refuses to comply with Einar’s needs, and he gets his revenge by betraying her to the secret police.

Þel takes place in the 1950s and 1960s. The highly stereotypical gender roles of the book are hollow, and the narrator’s male chauvinism seems desperate. We never find out why his friend took his own life. Everyone is a loser in this game.

Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir’s next novel Hringsól (1987; Circle) is framed by an elderly woman’s memories. The text revolves through different levels of time and space, forming a spiral in which the cycles become increasingly intense towards the top, which is the end of the narrative and the narrator’s life. The story is even more modernist than Þel because the text moves through temporal levels without any obvious transition; the narrative is told now in the first person, now in the third person; and the only thing the reader knows for sure in this maelstrom of reminiscences is the names of the characters – and they, too, can be misleading.

The book tells of a young girl who is adopted by a well-off, childless couple in Reykjavík. Her mother is dead and the family fragmented, but the girl would rather have lived in poverty with her father and siblings. The separation from her family is traumatic for her because she enters a loveless family in which she is increasingly treated as the household help and not as a daughter. The emotional relations between the members of the new family are warped and perverted, and the girl is ‘reserved’, from a young age, for her stepfather’s brother, ‘uncle’ Daniel. His Nazi sympathies, along with the housewife’s ambivalent attitude towards the imminent world war, reflects the girl’s subordinate position – like a Jew in the community of the house, she becomes both the target of aggression and a source of fascination.

The girl in the novel Hringsól is both attracted to and repelled by Daniel’s ‘incestuous’ attention. He is, after all, the only one who values her. This leads to an incredibly complicated love affair and, eventually, marriage: a story of mutual dependence and the sadomasochistic struggle for acknowledgement, power, and control.

The narrative’s desire for meaning and its simultaneously strong resistance to that meaning is expressed through the systematic repetitions of the narrator, which become almost manic when she refuses to dig any deeper and holds on fast to her illusions. As in Þel, the reader is swept along through an analytical process in which one question leads to another.

While Þel is set in the 1960s, the novel Hringsól begins in the 1930s, and Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir continues on her way backwards through history. The novel Hvatt að rúnum (1993; Rune Chant) takes place partly in the present day, partly in the eighteenth century, and partly in the early Middle Ages.

The History of Literature is Haunted

Hvatt að rúnum is about the twists and turns of love in a society characterised by violence and suspicion.

The first-person narrator of the novel is a middle-aged woman in Reykjavík who has unexpectedly gained a problematic room-mate. The room-mate is an eighteenth-century ghost called Stefan. This Stefan can be a nuisance sometimes, but the narrator puts up with him because she is fascinated by his tales. He tells her his story.

Stefan’s father dies suddenly while travelling with his son. The boy is taken in at a neighbouring vicarage. The priest is a learned but odd man who reads more than just his Bible. Amongst his books there is a romance from the early Middle Ages, which tells the story of the unlucky Diaphanus – the name means ‘the transparent one’. Diaphanus’ story is the third story on the third temporal plane of this complex novel.

The three stories in Hvatt að rúnum, each of which is set in a different time period and has a different main character, are tightly woven into one. If we keep to the ‘textile’-metaphor, we can say that a grandiose carpet is woven with patterns that are intermingled, repeated, contrasted, and elaborated on.

Each of the three stories develops an erotic threesome: two men – one woman, two women – one man. The problem with love is that it is not always directed at the ‘right’ people. Gender demarcations become just as unstable in the novel as do the boundaries of time and space.

Hvatt að rúnum goes beyond the limits of the novel and challenges its conventions, and at the same time deploys the material of literary history in a virtuoso, post-modern manner. One gets the sense that a novel could not support any more acrobatics through genre and time without becoming incomprehensible to non-experts – but Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir succeeds in surprising her readers every time, so who knows?

Dagný Kristjánsdóttir

Translated by Brynhildur Boyce