“In a marriage / you are the proletarian / and your lord and husband of the bourgeoisie. / Did you know that?” Wava Stürmer asks in the collection of poems Det är ett helvete att måla himlar (1970; It is Hell to Paint Heavens). Early on, she expresses a new woman’s consciousness and a clearly defined woman’s perspective. Wava Stürmer, who was born in 1929, published poems as early as in the 1950s, but it was in the 1970s that she gained range in her work, thanks to the impulses from the new women’s movement in Sweden. She wrote lyrics that spread throughout the Nordic countries, thanks to the record Sånger om kvinnor (Songs About Women), 1972. She also wrote for television and the theatre.

We are many

We are half

of all people in the city

Of all in the country

We are many

We are half

Yes, half of everyone existing,

are women

Wava Stürmer: Sångbok för kvinnor (1973; Songbook for Women).

In her prose, Wava Stürmer initially toes an everyday realist line, for instance in the novel Slå tillsammans (1976; Hit Together), which depicts a women workers’ collective. In the novel Väntans väg (1985; The Path of Waiting), she enters mythical time and through the female protagonist, who experiences a rift in time during an environmental conference, she sounds out a female cycle. Within the genre of lyrical poetry she creates a softly rhythmic long poem in Fågelvind (1982; Bird Wind), and in the collection of poems Så länge vi minns (1990; As Long as We Remember), which operates in the landscape of grief, she develops a language with a strong luminosity.

Wava Stürmer has played a large role in the alternative culture of her hometown of Jakobstad, and she was one of the driving forces when “Kvinnoskribentgruppen i Österbotten” (The Woman Writer’s Group in Ostrobothnia) was formed. The first Nordic women’s seminary, held in Sweden in 1978, inspired a group of Finland-Swedish women writers to form a writer’s group, which apart from Wava Stürmer consisted of several women writers who had all made their debuts in the 1970s: Solveig Emtö, Gunnel Högholm, Gurli Lindén, and Anita Wikman. All were born in the Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia and represent a region of Finland culture separate from the dominant culture of the capital city. They shared a short education, experience with low-wage work, a rootedness in women’s everyday life, and social commitment. In their prose, they are at first new realists and let their language be coloured by dialect tonalities and strong everyday references. Within the genre of lyrical poetry, they stay close to spoken language in syntax and choice of words, and introduce different variations on the theme of female rebellion. Some of them, Gurli Lindén and Anita Wikman, were active in the formation of the alternative publishers Författarnas andelslag (writers’ share-held publishers), created as a regional counterbalance to the commercial publishers in the capital Helsinki.

Solveig Emtö (born 1927) is one of a number of writers to make a ‘late’ debut in the 1970s. In three novels with an autobiographical setting, Rönnbär och flanell (1974; Rowanberries and Flannel), Krokushuset (1976; The Crocus House), and Det gula slottet (1978; The Yellow Castle), she depicts the working class girl Elvira and her upbringing at the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s in a small Ostrobothnian coastal city: Jakobstad in real life. Solveig Emtö homes in on Elvira’s language and reality. Elvira’s father emigrated to Canada, and the mother is remarried to an alcoholic who came to the town as a scab. The war begins, the men and the older boys go to the front lines, joys are few, worries many. Elvira is amongst other things exposed to the sexual advances of her stepfather. The relationship culminates in the third book, Det gula slottet, in which Elvira finally succeeds in putting him in his place. Solveig Emtö’s trilogy lives through the cheerful mood of the narration and through the depiction of Elvira in her shifts between terror, rebellion, and a joyous will to live.

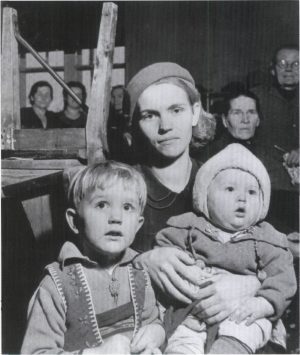

In her book about the warchild Pelle, Krigsbarn 13408 (1981; Warchild 13408), Solveig Emtö presents an intensively vivid contribution to the literature about the so-called war-children – approximately seventy thousand Finnish children who were sent to Sweden during the Second World War. Pelle is well cared for by his new family in Sweden, but the terror and disintegration he has experienced makes his sense of identity totter when he returns to Finland. Linguistically, Solvig Emtö is entirely apace with her Pelle, following him into his child’s language and his Ostrobothnian dialect. In the novel Eldvagnarna (1987; The Fiery Chariots), she depicts the adult Pelle’s life in a narrative in which the present is shattered by images of unmitigated terror.

“I’m not her boy. I’m 13408. I will travel the world. Father plays the brass horn at the grave, the grave. Ow, careful mother, so that Pelle doesn’t break.”

Solveig Emtö, Krigsbarn 13408 (1981; War Child 13408).

“I was born, you see / on the wrong side of society, the wrong gender, the wrong class / and all of this I have borne as a painful burden, in spite of being innocent”, Anita Wikman (born 1938) writes in the collection of poems Därför (Because), 1977. There is a rebellious strength in her poems; she expresses in words the women’s reality that had not previously received attention in Finland Swedish literature. In the collection Väntrum (Waiting Room), 1979, she depicts a gynaecological operation and the fellowship of women at the hospital. It is a song of songs treating of the woman’s body: “We stand in the shower bent by our wounds / and with sagging breasts open to each other / We laugh in collusion when our movements / tire and sweat shows on our brows”. Sången om Taimi och Sonja (1984; The Song about Taimi and Sonja), 1984, has the subtitle ’poetic narrative’. The women Anita Wikman depicts are the Finnish speaking Taimi and the Swedish speaking Sonja. They have no livelihoods in Finland but must move to Sweden. Anita Wikman uses a version of the old verse form runometer (trochaic tetrameter) found in the Finnish national poem Kalevala (Eng. tr. Kalevala). The metre lends the depiction a hint of ancientness, while also bringing forth some of the mythical depths of folklore that Anita Wikman is trying to reach. In her poetic narrative, the women of emigration and of heavy care work have an epic of their own.

When Anita Wikman, who calls herself a ’proletarian village-writer’, looks at the woman-man relationship, it is always with an eye to social conflicts. Both women and men have difficult starting points, both are worn down by heavy labour; women, children and the old fare poorly, but there is an irrepressibly positive force for life to counter the darker elements in the women’s everyday life that she depicts.

In the autobiographical trilogy Kråkvals (1987; Crow Waltz), Kråköga (1991; Crow’s Eye), and Vingklippt (1996; Wing-clipped), Anita Wikman depicts a shoemaker’s family in an Ostrobothnian coastal city and the socialisation of girls brought up in the shadow of war. It is not just the war experiences that threaten the little girl’s world, but also the father’s brutality and incestuous advances. Anita Wikman depicts the hardest experiences in images that point to an opening for the little girl to find healing and a creative imagination.

Gurli Linden (born 1940) has moved from women’s realism to women’s myth in her works. In her first novels, Bli till (1976; Becoming) and Första damernas (1979; First Ladies), she depicts women’s existence and upbringing in the Ostrobothnian village. Liberation comes through search and crisis, while creating the new begins when old prejudices are broken. In her later prose, Maras ö (1984; Mara’s Island) and Framtid (1989; Future), she turns to a mythical woman’s time and writes in a slightly archaic style rich in imagery. She gives a language to vision and Utopia that alternates between clear images and evasive visions. In her poetry she has moved along a continuum from typical New Simplicity to suggestive imagery, as in Tigerns öga (1983; Eye of the Tiger) and Grodan (1993; The Frog).

Marching and Growth

Denna värld är vår. Handbok i systerskap (This World is Ours. Handbook in Sisterhood), 1975, is the triumphant title of the book that introduced the new woman’s movement in Finland. The authors, Birgitta Boucht and Carita Nyström, both born in 1940, have an academic background. The first part of the book is a description of the ideas of feminism. In the second part they speak out more privately, each in a suite of poems. After their joint debut they separated. They have a wide spectrum of womanhood in common, but emphasise different aspects: for Birgitta Boucht marching and change become the main themes, while for Carita Nyström is it growth and re-growth.

Birgitta Boucht’s Långa vandring (1981; Long March), is written the year before the peace march to Paris in 1981. The long march of the women begins ‘in the campfires and storytelling times’, and moves from mythical time to the present. Lyrical close-ups alternate with narrative poems, joy, and adversity.

The old women’s hoarse guffaws in the night.

Their patience, stubbornness, dry hardiness.

We were each other’s daughters and mothers.

The pattern never very obvious …

But the old women’s furrowed faces

were always inside us.

And their bright eagerness:

we are leaving, what are you waiting for girl chits!

Birgitta Boucht, Långa vandring (1981; Long March)

Glädjezon (1986; Joy Zone) is about the 1981 march to Paris and the 1983 Washington march, two marches that Birgitta Boucht participated in. The depiction in poems and prose does not give way to the difficulties of the march, but expresses the joy of sharing one’s emotions for the world with others: “Joy Zone. Only the march will take us there.” The collection of poems De fyrtionio dagarna (1988; Forty-Nine Days) – the title of which is taken from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and indicates the time between a human being’s death and rebirth – becomes an intense “journey in the transparent landscape of grief”. “I explore grief” it states, but it is also a journey in a language that in some places has been eradicated, with images that mix acrimony, nervousness, and love. In Inringning (1991; Encirclement), which contains both poetry and prose, Birgitta Boucht brings out grotesque irony and black humour. She begins in a landscape of crisis, encircles a childhood in small rooms, and ends with an image of paradoxical simplicity: “it breathes”.

In her works Carita Nyström contrasts growth and re-growth with a one-sided economic growth that has destructive consequences for people and for the environment. In the collection of poems Ur moderlivet. Dikter om havandeskap och samhälle (1978; From the Mother’s Life. Poems about Pregnancy and Society), she follows the prenatal development and birth of a child. A retrospective look at her development, from the first contacts with red-stockings in Denmark to a feminism with an ecological signature, is presented in Återväxt (1982; Regrowth), with the sub-title “Thoughts about reproduction”, which layers debate, diary, and poem. In the poetry collection Huset i rymden (1984; The House in Space), she alternates between intensive prose poetry and lyrical annotations, and seeks a holistic language that can encompass her ’demons’ as well. The novel Den förvandlade gatan (1991; The Transformed Street) provides autobiographical background. Carita Nyström explores the girl Sanna’s experiences as a war-child. “Even she belonged to the wounded generation.” In 1944 she stands alone on a train platform in a foreign country with a placard, with her name on it, on her chest: “Terror is an abyss, and it gapes. The girl stiffens without tears. She no longer feels her body. She feels nothing. It is empty, just empty.” After her return from Sweden, Sanna finds it difficult to find a place in her family, and it is not until she gets in touch with her encapsulated terror as an adult that she experiences liberation.

Birgitta Boucht and Carita Nyström met again in the epistolary book Postfeminism (1991), in which they share their experiences of the 1970s in a time that has been called post-feminist. Old demands for solidarity and generalisations must be broken down and replaced with “the solidarity that actually is offered in the real world and everyday life”, Birgitta Boucht finds.

About Inga-Britt Wik

Inga-Britt Wik (born 1930), herself a native of Ostrobothnia, made her debut as a lyrical poet in 1952 with the sensitively recording collection Profil (Profile). Her following collection, Staden (1954; The City), builds on impressions from a visit to Paris: city life, the colourful, cosmopolitan everyday in the streets, the lively pulse of the day, the impetuous intensity of the nights, and the feeling of loneliness mixed with experiences and thoughts in the female poet’s world. In her mind her childhood’s ’Ostrobothnian’ landscape rises, the open plain where earth and sky meld together at the horizon. Out on the plain all paths lead somewhere. There is always a destination or a guiding marker to plot a course by.

The confrontation between two such different types of experience, the big city and the landscape, drives the poetic speaker to seek a synthesis, “my vulnerable love”. “The love is incomplete, always larger or smaller / than its opposite / It is a possible resemblance between us all / and never the same”. The difficult adjustment between those huge contrasts will later become one of Inga-Britt Wik’s recurring themes, and it shows both in the oppositions of the outer world and in the inner resistance and longing for love.

In the collection Fönstret (1958; The Window), the city poet’s voice has been changed, the joy of writing and the assured experience of self has receded. Terror becomes the main motif. It shows itself to the married family woman as the ironic and twisted side of love.

From this empty space the self attempts to reawaken to life through fantasy images from her childhood. She remembers the contact and closeness, the sensuality, but the body, mouth, hands, and face remain insensitive and heavy. Just a taste of dust remains. Once again Inga-Britt Wik shows us jarring contrasts and a dream of synthesis. But in the poem there is no reconciliation, the body and the heart have already decided to leave the empty marriage. And the collection ends with a recurring motif, the small room, and with poems about children, in which the child’s body, the mother’s and child’s mutual breath, becomes life-giving. The child theme is continued in the collection of poems Kvällar (1964; Evenings): “The little face / glows so quietly / within my body // All boys that / I know / sleep now”.

In the collections from the 1960s, Wik continued the depiction of the family and the working woman. The distance between the far-reaching, rhythmic poems in Staden (1954; The City) and the sharp aphorisms in the collection Långa längtan (1969; Long Longing) is great, but the thematic similarity shines through: where is the connection between a woman’s life, love relationships, and social life, and the greater world’s demands for involvement. Yet again she looks to Ostrobothnia, to the wisdom of the old women there, to find a perspective that can create a synthesis between the two poles.

A new productive phase during which Inga-Britt Wik experimented with epic and dramatic forms began in 1977 with the collection of poems Mänskliga människor (Human Humans). The novel Ingen lycklig kärlek (1988; No Happy Love) tells of the marriage of two young intellectuals in the 1950s. Her work with the older Finland-Swedish Eva Wichman’s posthumous prose writings in 1977 became, according to Wik, her incentive to resume her own writing. In her production between 1970 and 1990, which is strong and colourful, filled with people and shapes, she rediscovers the boldness and openness of her debut collection. The commitment, which is so obvious in Långa längtan (1969; Long Longing), becomes visible once more, now as a part of the middle-aged woman’s self-consciousness and self knowledge.

“In my poems I write about my own experiences: sometimes I have called it documentary poetry. I strive for honesty and hope that what I give of myself reaches someone else with similar experiences. If I must be classified then ’pugnacious romantic’ comes close”, Agneta Ara (born 1945) writes in Finlandssvenska kvinnor skriver (1985; Finland-Swedish Women Write).

In the collections of poems Omfamningen (1982; The Embrace) and Korta stund (1983; Brief Moment), Agneta Ara nakedly and unsentimentally depicts a young marriage, pregnancy and the birth of a child, everyday and married life, and divorce.